The Scarf and/or Sweater of Solomon; or

High Doc-Tane

(a recap by Will Kaiser)

Title: The Wisdom of Solomon

Airdate: March 7, 1977

Written by Scott Swanton

Directed by William F. Claxton

SUMMARY IN A NUTSHELL: When Todd Bridges comes to town, the Grovesters are surprisingly nice to him; but he winds up leaving because of racism anyway.

RECAP: A couple notes before we start this one.

First off, if you’d like to hear Melissa Gilbert and Todd Bridges reminisce about this episode, head over to this week’s Modern Prairie Knitty Gritty podcast. A very fun conversation.

“The Wisdom of Solomon,” as you probably know, is another Little House story about racism – one of the best remembered of them all, in fact.

This one’s shock value has actually increased since the 1970s. Of course, Little House being a children’s series that features racism, child abuse and mortality, plague, sexual assault, suicide, addiction, and other horrors on a weekly basis, that’s to be expected with a lot of these stories.

But “The Wisdom of Solomon” stands out, even in a crowded field.

This is because it contains a slur which over time has grown to eclipse virtually all other slurs and profanities in its potency.

I will not be quoting the word here, but as you probably already know, it appears in a stunning scene that is this story’s centerpiece.

As long as I have your attention, I know some people dislike looking at art of the past through lenses of the present. But I’d argue by now, that approach is essentially built into discussion of Little House on the Prairie in any form (as separate from discussion of the real-life Ingalls family, who, you may remember, existed).

Think about it. The TV series is a look back at the books, through a very 1970s lens. The books were themselves a “remembrance” of an era long past by the time they were published. And I’m writing this in 2023, watching with people twenty or thirty years younger than I am. All things considered, a multi-generational approach isn’t really that off-the-wall, is it?

Well, on we go. I’ll try not to let this recap get too heavy, since after all Walnut Groovy is intended to be silly fun, not a lecture.

Anyways, perhaps the most astonishing thing about this episode is that while it includes that word, the streaming version of this story is still only rated 7+! I think even Carrie saying “damn” got a 13+.

But enough said about that. We have a curious factoid with which to begin this week. This episode was originally preempted in NBC’s schedule by something else. It must have been something very important to bump Little House.

What was it, you ask? The Olympics? An address by newly elected President Carter asking Americans to turn their thermostats down?

No, it was a documentary called The Mysterious Monsters, which examined the search for Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster.

WILL: Ooh, do you remember when they used to show crap like that on TV?

DAGNY: Yes. That and Christmas specials were the only times you’d be happy your shows got bumped.

Host Peter Graves called The Mysterious Monsters (no doubt accurately) “[maybe] the most startling film you’ll ever see.”

Little House returned the following week.

We open on a field. The day is hazy.

In the field are a man and a woman. A little boy comes over a hill in the distance and runs towards them.

Then we see a buckboard coming in hot pursuit.

It isn’t. Plus, David Rose’s music is “scampering” rather than scary, so we know the kid’s not in real danger, physically anyways.

DAGNY: Driving across their freshly tilled field is NOT COOL.

The camera jumps closer, and a man gets down from the buggy, yelling at the kid.

We see the driver is white and the other three people are Black. This represents a 300-percent increase in total Black characters in the series so far.

(Don’t get too excited. Black characters have only appeared in 3 percent of the stories to this point, this one included.)

The white guy calls the kid “boy” a couple times, and the woman, who’s hugging the kid, begs the man’s forgiveness.

The white man shouts that the kid stole a book from the steps of a school.

ROMAN: Stole a book? Just like Busby!!!

I’m not sure what this guy has to do with it – is he school security or something? He’s not dressed like a teacher, or screaming “silence” or “I must have order” or anything else indicating he is one.

He’s identified in the credits simply as “Man,” so that’s no help.

This “Man” is kinda familiar-looking, and the actor, Russ Marin, was in a lot of stuff, including Bonanza, The Waltons, Highway to Heaven, and a number of soaps.

Marin also was in some interesting and weird films, including Mommie Dearest, Brian De Palma’s Body Double, and – you may know this one – the Matthew Labyorteaux horror vehicle Deadly Friend, in which Kristy Swanson plays a sort of zombie robot, or maybe a robot zombie. (I forget the nuances of that one.)

I do remember it’s not for everyone.

“Man” demands to know the kid’s name – which we learn is Solomon Henry – and says if there’s any more trouble from him, he’ll make sure the Black family is driven out of “Emmetsburg.”

Emmetsburg, Iowa, is a real place, close to the Minnesota border and about 100 miles south of Walnut Grove. (This is the first mention of an Iowa location in the series, I believe.)

To my knowledge, Iowa has even fewer mountains than Minnesota in real life; but you wouldn’t know that from Little House on the Prairie.

“Man” leaves. He’s not really important to this story, so goodbye to him, and let’s get to know the other characters.

All three of the remaining actors are familiar-looking too.

The mom, who wears a classic-era actress’s “long-suffering” expression, starts yelling at Solomon about stealing the book, saying he’s ruining the “fresh start” the family is trying to make after moving here (she doesn’t say from where).

Mrs. Henry is played by Maidie Norman, who really was a classic-era actress. You might recognize her from many things. As a young woman, she appeared on The Jack Benny Program and Amos ’n’ Andy on the radio. (You’d have to be pretty old to recognize her from those, no offense if you do of course.)

Norman went on to TV roles on Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone, Dragnet, Ironside, Days of Our Lives, Mannix, Adam-12, Kung Fu, Marcus Welby, M.D., The White Shadow, Good Times, The Jeffersons, and Amen.

She played the canny but unfortunate maid in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, and she was in Airport ’77, one of those seventies all-star disaster movies.

Finally, she was in Halloween III: Season of the Witch. (That one’s a real oddity, I can tell you.)

Oh, one last thing, she was a member of the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, too.

Anyways, Solomon says, “I want learnin’, Mama – I wanna read!”

Todd Bridges probably needs no introduction to viewers of an age to remember this show. An amazingly expressive and telegenic child actor, he’s known best from Diff’rent Strokes.

Diff’rent Strokes told the story of two Black children, Arnold and Willis, adopted through some contrivance by a wealthy old white man.

Bridges played Willis, the sensible older brother. Actually, now that I think about it, Arnold and Willis had a Laura/Mary dynamic, minus the blindness, the dead babies, and the hating each other in real life.

Diff’rent Strokes was a cultural force. With other shows (like Little House!), it pioneered the device of dealing with contemporary social issues, and baking a moral message into light televised entertainment. It’s one progenitor of what became known as the “Very Special Episode” TV phenomenon in the 1980s.

Diff’rent Strokes was so popular, First Lady Nancy Reagan appeared on the show for an anti-drug storyline in 1983.

Todd Bridges’s character was the frequent target of the show’s still memorable catchphrase, “Whatchoo talkin’ about, Willis?”

I liked Diff’rent Strokes. I haven’t watched it in many years, but the theme song certainly stands up.

For reasons that will be obvious as we get into this one (spoilers: he’s an incredible little actor), Bridges became a big star as a small child. In addition to Diff’rent Strokes, he also appeared in Roots, The Waltons, and The Facts of Life (again as Willis).

Love Boat, too.

Being a child star chewed him up, though, as was too often the case then as now. He had some well publicized drug and legal problems as a young man, but cleaned up. Then he appeared in a lot of reality TV junk, some movies I never heard of, and Everybody Hates Chris, on which he had a semi-regular role.

Anyways, Solomon says he wants to attend the school, but his mother says he can’t, because it’s for white kids.

“Why?” says Solomon. “If we free, why can’t I?”

“You’re free to be what the white folks want you to be,” says Mrs. Henry.

(I realize a good percentage of the populace these days have their heads up their asses about race, but Mrs. Henry hits the nail on the head here.)

She goes on to note in their case, “freedom” means being given a patch of worthless land and calling things square after generations of slavery.

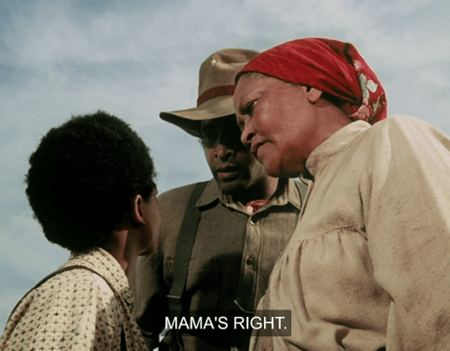

“Mama’s right,” says the man. (Not “Man” – the, er, other man.)

Apparently he and Solomon are brothers, despite what seems to be a large-ish age difference.

Well, more than seems: Bridges was eleven, and the actor playing his brother, David Downing, was 33. (Downing appeared on All in the Family, What’s Happening!!, Father Murphy, The Jeffersons, Designing Women, 227, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Roc, JAG, and The Bernie Mac Show.)

Incidentally, Maidie Norman was 64, meaning Mrs. Henry would have been 31 when the older brother was born (okay), but 53 when Solomon was. I’m a little dubious about that one.

Well, Mrs. Henry tells Solomon he can either do things the white man’s way or he can hit the road. Solomon takes off running, but when the brother says he’ll catch him, she says, “No – he done made up his mind.”

It’s a Skillet Scramble of the same conflict we had in “I─── Kid” just a couple weeks ago, with different dynamics and incidentals, of course.

Only then do we get the title, as tiny Solomon climbs a hill, to some unusual piano music from the Rose. Sounds like a fake Mozart rondo, or something.

The title of course is a reference to the Biblical King Solomon, known for his wisdom. (He was crazy like a fox.)

We see this episode was written by a Scott Swanton.

He’s new, but I think he’s the son of Harold Swanton, who wrote the Burl Ives one and the Irish funeral one.

DAGNY: Was he Black?

WILL: Well . . . no, not really.

Scott Swanton also wrote a handful of other TV things – nothing I’ve ever heard of, though, except I suppose an episode of Angie Dickinson’s Police Woman.

We then cut to a town. Emmetsburg? Looks like Mankato to me.

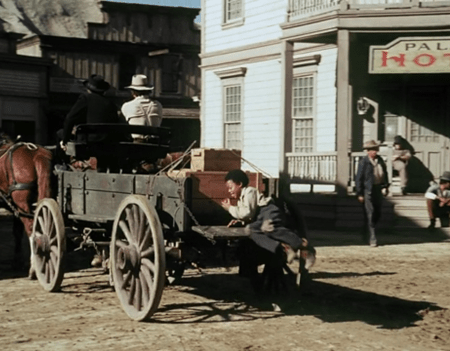

We see the Alamo Tourist from Pee Wee’s Big Adventure driving by, and then we notice Charles unloading the Chonkywagon.

By the way, Claxton is back as director.

Charles is delivering crates of apples (Red Delicious, yuck) to a store. Must be fall, then? We figured the saga of “To Live With Fear” occurred over the months of September and October, but I suppose technically it could still be late fall of 1876 (in the D timeline). Looks awfully warm for late October or early November in Minnesota, though.

A grumpy old grocer Charles addresses as “Mr. Kramer” receives the fruit, and we see Doc Baker and another man carrying some boxes to the wagon. Apparently Charles has some company on this delivery trip.

Doc’s companion, we see, is also a Black man. Doc says, “I appreciate the help, Dr. Tane.”

A brief conversation reveals that Doc has come along to pick up medical supplies, and that he’s also giving this Dr. Tane some leftover “free samples” he received from pharmaceutical companies. (Was that a thing even then?)

Dr. Tane says he’s grateful to get medicines for his practice, no matter where they come from.

WILL [as DOC BAKER]: “Ever try that Dr. Briskin’s Homeopathic Remedies?”

Doc says he doesn’t understand “why the government doesn’t send proper medical supplies to the Reservation.”

Dr. Tane laughs at Doc’s naïveté, saying, “Why should they? It’s just for Indians.”

(We’ll deal with which Reservation he might serve in a bit.)

Dr. Tane says, “I’ll be by as soon as I can for those samples, Doctor, and thank you,” and Doc replies, “You’re welcome, Doctor.”

WILL: Do doctors really call each other “Doctor” all the time?

DAGNY: Yes, they do. It’s quite obnoxious, actually.

We shift gears then when grumpy Mr. Kramer starts yelling . . . and we see little Solomon is there, trying to steal an apple from a barrel. (So presumably this is Emmetsburg? Pretty far south for Charles to go to deliver apples.)

The grumpy old man is played by Frederic Downs, a veteran of Hazel, The Addams Family, Gunsmoke, Bonanza, Mannix (God, who wasn’t on that?), The Waltons, and The Misadventures of Sheriff Lobo.

He also was in Bug, a movie about super-intelligent cockroaches that’s a favorite of my friend Raja’s (mine too).

Charles intervenes and buys Solomon an apple himself, telling him, “The next time you want one of these, you ask for it, all right?” (Ask who?)

Solomon smiles, unable to believe Fate sent this idiot who finds shoplifters charming.

Then we get a shot of Charles, Doc, and the Chonkies driving through the city streets.

They pass businesses that include J.M. Collins, Gunsmith, and the Palace Hotel – last seen in “To See the World.” (So it is Mankato after all! But how did Solomon get here from Iowa?).

As they go by, Solomon Henry chases after the Chonkywagon and stows away on the back of it, like some Dickensian imp or urchin.

I love that the second he gets up on the wagon, Todd Bridges takes a big bite out of his apple.

Without much further ado, we then see the Ingalls wagon driving back into Walnut Grove.

Unusually, the wagon is coming into town via the “shortcut” behind the Mill that the girls often take to get home from school. I don’t think we’ve ever seen a vehicle on it, but I could be wrong.

Solomon jumps off the back of the wagon, which is also odd. If they’re coming from Mankato, it would be a two-day trip at least. Where did he hide when they camped down for the night? What if he had to go to the bathroom? And how did he know they’re not just passing through this town?

None of this really matters, of course, so never mind me. Solomon sees a bunch of kids playing in front of the school. Apparently it’s recess time, though the shadows are pretty long. (I guess if it’s late fall, this makes sense.)

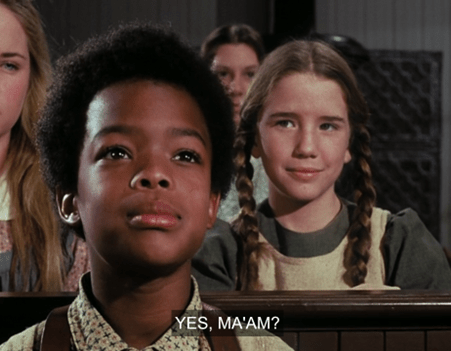

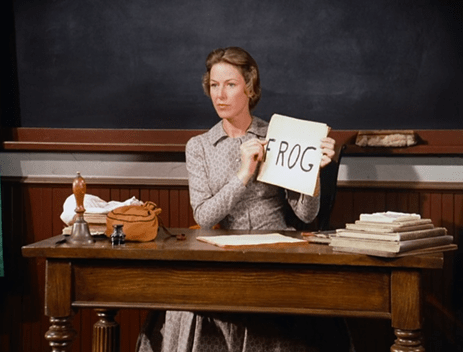

After recess, Miss Beadle makes the kids recite “Casabianca,” better known (?) as “The Boy Stood on the Burning Deck.”

(You’ll recall “Casabianca” was one of the works Laura’s old boyfriend Jason R. recorded on the phonograph. I wonder whatever happened to him? Maybe he parlayed his wax cylinder into a recording career.)

Anyways, if there’s any thematic significance or relevance to this choice of verse, I’m missing it.

In the gallery today are a core group of classic student characters: Laura, Mary, Nellie, Willie, Cloud City Princess Leia, Not-Joni Mitchell, Pigtail Helen (without pigtails again), Mona Lisa Helen, the Kid with Very Red Hair (mean one), and a few not-Carl Sandersons.

Miss Beadle is full of energy. She struts up and down the aisle actually conducting the poem.

WILL: She’s kind of an odd person.

The camera shows us Laura, who, like a cat in an animal behavior study, is “opting not to participate.”

The Bead zeroes in on this at once.

OLIVE: I’m glad I don’t get yelled at every time I don’t pay attention.

WILL: I yell at you every time you don’t pay attention to this show.

Then Laura notices a face peering through the window. It’s Solomon.

WILL: Please don’t let her think he’s a hobgoblin or something.

Laura rises from her seat to stare, and Miss Beadle shrieks “Laura Ingalls!”

ROMAN: It’s like that Twilight Zone where he sees the thing on the wing of the plane but no one believes him.

Miss Beadle tells Laura to stay after school. If you watch closely, you can see Not-Joni Mitchell and Cloud City Princess Leia laughing at Laura behind her back, like the terrible people they are.

The Bead then manages the feat of resuming conducting the poem whilst simultaneously shaking her head in disapproval. (Charlotte Stewart is super-talented that way.)

DAGNY: Poor Bead.

Walking home with Mary, Laura reports her punishments, which include a note to Ma and Pa.

OLIVE: Miss Beadle wrote a NOTE? That’s hardcore.

Laura and Mary then debate whether it’s better to call the mysterious kid she saw a “Black boy” or a “Negro.” (Might be best just to ask him his name next time you see him.)

The girls jibber-jabber for a while, then suddenly stop talking, which is weird.

Then Laura gets a bug on her head.

That night, Laura goes out to talk to Pa about the note, and, after a fair bit of nonsense, she does so.

The two have a surprisingly generic conversation about trying harder at school. You can tell Swanton the Younger is new to these characters.

That said, the chemistry between Landon and Gilbert here burns brightly.

Charles mentions one particular of the note: viz., that Laura is required to learn a long poem to recite in front of the class.

Laura then goes out to collect eggs. (At night? I don’t think we’ve ever seen that.)

When she opens the chicken coop, she finds Solomon hiding within.

To her credit, Laura jumps down onto the floor to get to know him.

DAGNY: What is he doing?

You see, Solomon is holding an egg up to his mouth. Laura asks him the same question, and he says, “I’m sucking a egg.”

OLIVE: Um, what?

ROMAN: Yeah, what?

Egg-sucking is a weird phenomenon I mostly associate with old-timey entertainments like Old Yeller and Johnny Cash songs.

In fact, this might be the first time I’ve ever seen it depicted onscreen.

Wikipedia says, “Before the advent of modern dentistry (and modern dental prostheses) many elderly people . . . had very bad teeth, or no teeth, so that the simplest way for them to eat protein was to poke a pinhole in the shell of a raw egg and suck out the contents.”

And that’s about as far as I want to research this topic.

Laura then gets the cringeworthy line, “Are you a for-real Negro person?”

(I’m pretty sure using “for-real” as a descriptor wasn’t a Nineteenth-Century thing.)

DAGNY: I wonder why Laura’s braids are over her ears like that. Do you think she had her ears pierced?

She rubs Solomon’s cheek, presumably to check if he’s actually a white kid in blackface. Blackface “minstrel shows,” in which white performers wore stylized makeup to play exaggerated Black characters, were popular in the U.S. throughout the Nineteenth Century, and even later. (Wikipedia calls them “the first uniquely American form of theater” and says “by 1848 . . . they were the national artform.” Nice, huh?)

Charles Ingalls actually performs in a minstrel show himself in Little Town on the Prairie, in a scene which thankfully was never adapted for the TV series.

Laura and Solomon chit-chat for a while. She says she’s never seen a Black person, and he tells her briefly about following Pa home after the positive encounter with him.

Right on cue, Pa appears in the doorway.

ROMAN: Is he going to pitchfork him like Jasper?

Pa seems unsurprised to see Solomon, which is surprising in itself. Isn’t it?

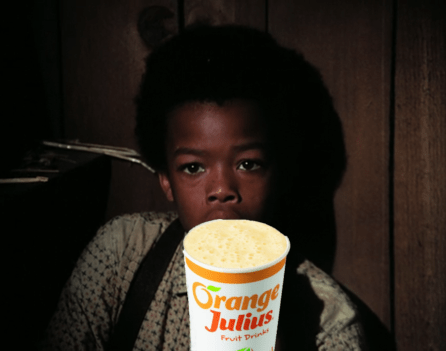

Solomon confesses to sucking the egg, and Pa says, “Oh, I see. Well, in that case you’ll probably be wanting a glass of milk.”

WILL: How about an Orange Julius? Doesn’t that have raw egg in it?

They bring Solomon inside, Laura gloating that she’ll now be able to prove to the Bead she was right.

ROMAN: Is she gonna bring him in for Show and Tell?

OLIVE: She will. That’s such a Laura thing to do.

We cut to Ma giving Solomon some milk in the common room. She’s quite nice to him.

OLIVE: So she just hates Indigenous people, not Black people, huh.

Laura and Carrie stare at Solomon quite rudely.

Through this scene, Laura says several times how exciting it is to have “a real Negro person” in the house.

Pa says they should “get down to cases” – an expression that was new to me. I couldn’t find an origin for it, and I can’t say if it was in use by this time or not. (I’m sorry, reader. I’ve failed you.)

[UPDATE! Reader and Friend of Walnut Groovy Midrael Viejo of Tucson, Arizona, sent us the following explanation and citation, which I missed in my researches: “The noun cases [in getting down to cases] apparently alludes to the game of faro, in which the ‘case card’ is the last of a rank of cards remaining in play; this usage dates from around 1900.”]

[Well, even if the expression doesn’t quite go back to the 1870s, it’s a nice touch, since faro these days is closely associated with the Old West, playing a major role in Deadwood, La Fanciulla del West, and other such entertainments.]

Anyways, Solomon says he’s eleven years old, Todd Bridges’s real age. (Melissa Gilbert was twelve, and by my calculations Laura the TV character is somewhere between nine and 25 years old in this story.)

WILL: Does he have a runny nose?

DAGNY: He does, and you can tell Karen Grassle is distracted by it, because she keeps touching hers.

Pa asks Solomon if his family is back in Mankato. Solomon lies and says they’re all deceased. He says he was born in Mississippi and then lived in Virginia “for some time.” (Presumably he means Virginia the state, not Virginia, Minnesota, a town 325 miles northeast of Walnut Grove.)

Carrie stares at Solomon very seriously during this entire scene.

OLIVE: Please don’t let her think he’s a hobgoblin or something.

But no, Carrie doesn’t speak at all, thank God.

Solomon tells Pa he has farm experience. “I’m a lot stronger than I look,” he says. “I work a two-mule team all day, and a cross-cut saw that’s twice my size.” (Solomon exaggerates throughout this scene, so it’s unclear how accurate this claim is. It could be true, or true-ish.)

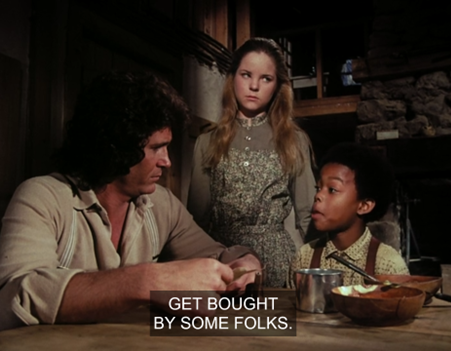

Solomon says he could learn housework too, then he hands Charles a piece of paper.

Pa reads:

For sale: Healthy boy, eleven years old, eighty-seven pounds. Good for house or field. Very obedient.

Pa looks embarrassed, but Solomon is proud. He says the paper actually refers to his father, not himself, but the description fits him perfectly too. (Yes, it is kind of a coincidence.)

Solomon says he would be an excellent investment if Charles is interested in buying a slave.

Mary watches this conversation neutrally.

DAGNY: She looks like she’s considering it.

WILL: Yeah, no wonder she turns out to be a Confederate sympathizer.

Unsure what to say to this, Charles says Solomon’s father’s paper is dated 1854. Now, if Mr. Henry was eleven in 1854 and it’s 1876 now, that means he would only be 33 years old if alive.

This can’t possibly be right, since we deduced above that Mr. Henry’s other son (unnamed in the story as yet) is 33 years old himself.

Anyways, Pa tells Solomon President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation banned slavery. (Juneteenth has just passed as I’m writing this.)

Solomon suggests this is unfair, that a person “oughta be able to sell what’s his” – even his own body – “whether Lincoln likes it or not.”

OLIVE: He thinks it would be fun to be a slave again? Sure.

WILL: He’s only eleven, he probably wouldn’t remember being one.

Solomon says he would use the money from his purchase to enroll in a school, because regular schools don’t take Black students.

Much impressed by this little chatterbox, Pa says Solomon can stay in the soddy for the time being, and says tomorrow he’ll talk to Miss Beadle about going to school.

Solomon politely thanks Ma for the dinner and exits, and Laura exclaims “A genuine Negro person!!!” for like the fiftieth excruciating time.

Out in the soddy, Solomon suspects Pa doesn’t actually have enough money to buy him. (Of course, Charles, having spent the past two months neglecting his crops, and having just given all his blastin’ cash to the Mayes Clinic, probably doesn’t!)

(Incidentally, the price of slaves varied widely. A New York Times article from the beginning of the Civil War found prices starting at $13.50 or lower in today’s money ($7 Confederate), though the average range seems to have been more like $1,000 to $10,000 in 2023 dollars.)

(In Minnesota, which despite the accents of half the actors in this series is actually a northern state, slavery was technically illegal after 1820, but the law wasn’t always observed or enforced.)

Anyways, Solomon shrewdly says he’d be willing to sell himself to Charles “on time” (i.e. on credit).

OLIVE: Is Pa going to make one of his “cash on the barrel” speeches?

All Pa does is giggle at the kid’s chutzpah and say goodnight.

WILL: Solomon should stay up trying to read and start a fire.

Later, Caroline looks out her bedroom window, worrying Solomon is cold in the soddy. (More evidence this story is set in late fall.)

Charles says he’s going to take Solomon to town tomorrow to get him settled at school.

After that, he says, he’ll “drive into Mankato” to investigate Solomon’s origins. It’s clear the production team has forgotten how far away Mankato is from Walnut Grove.

Anyways, as is often the case in their, um, boudoir, Caroline’s in a flirty mood. She gets into bed and starts stroking Charles’s chest, shoulders and, um, the like.

Of course, she veils her appetites (thinly, but still) with smalltalk about how great Solomon is.

Once again, clueless Charles doesn’t take the hint, saying goodnight and turning the light out.

Almost immediately, Charles begins giggling happily in the darkness, though.

He says, “He’s gonna let me buy him on time!” You know, as if that’s why he’s laughing.

But that’s gotta be just in case any kids are listening. You and I both know, reader, he’s laughing because she’s touching his penis.

Well, then we cut to Charles, adorably giving Solomon a bath in a rain barrel.

In a hilarious bit of business, Laura comes running in, then spins in embarrassment when she sees Solomon’s bathing.

Pa dries him off, noting today will be Solomon’s first day of school.

I’m not going to post a picture, but there is a moment when you can see Todd Bridges is wearing shorts for his bath.

Solomon says where he’s from, something terrible happened to a teacher who let Black kids into an all-white school.

Charles says, “Well, don’t you worry about that. Nothing’s gonna happen like that in Walnut Grove.”

DAGNY: How can Charles think this is going to go well?

WILL: I know, after the whole Spotted Eagle fiasco?

ROMAN: Maybe a rock hit him during the cave-in and he got amnesia.

After a commercial break, we see the American flag being raised in town. (This episode is making a larger point about America, you see.)

Charles drives up in the Chonkywagon to drop off Laura, Solomon, and Mary. (In order of his favorite to least favorite.)

A bunch of kids swarm the school, though the shadows are long again and it really doesn’t look like morning to me. Did they film this one at a funny time of year, or something?

And then, Gawd help us, who should Charles and Solomon encounter on the school steps but Harriet Oleson?

Mrs. O gawks at Solomon with a horrible fascination.

ROMAN: Please don’t let her think he’s a hobgoblin or something.

After the kid goes inside, Mrs. Oleson tells Charles only kids whose families live in Hero Township may attend school in Walnut Grove. (When such a policy is used to keep people of color out of a community, it’s what’s some would call “institutionalized racism,” even if its language isn’t discriminatory on its face.)

Mrs. O cites this policy with the authority of a school board member, and she says she’s citing it with the authority of a school board member.

(What she’s actually doing at the school right now remains a mystery.)

Then Charles smirks and says that restriction doesn’t apply, because “Solomon is my son by a former marriage.”

Mrs. O runs off squawking for Nels. (MacG is the greatest.)

WILL: What did you think of that? It’s kind of a bitchy joke for Charles. I’m not sure I buy it.

DAGNY: It is a little out of character, but I liked it. Pranking her is the best way to deal with her, anyway.

Inside, Charles and Miss Beadle agree there’s absolutely no problem with enrolling Solomon, because this week they are both 1970s liberals beamed back to the pioneer days by means unknown.

Miss Beadle compliments Charles on his white-savior personality disorder, which we’ve had call to comment on in the past ourselves.

The Bead enters the classroom.

Everyone we saw earlier is here, plus there are a few new faces, including what appears to be a brother-and-sister matching set with sharp features and paranoid expressions.

Miss Beadle introduces Solomon to the class.

When Laura and Mary are the only ones to say hello, warning lasers ignite in the Bead’s eyes and she says, “Don’t you have something to say?”

Cruel but no fools, and remembering the Bead’s moods can mean life or death, all the kids say “Hello, Solomon.”

Miss Beadle skips the “formal name” onboarding she usually puts incoming students through, and tells Solomon to sit down after just one or two perfunctory questions.

And here we go. Trigger warning, brace yourself, however you want to put it, here we go into the scene that contains that very strong racial slur.

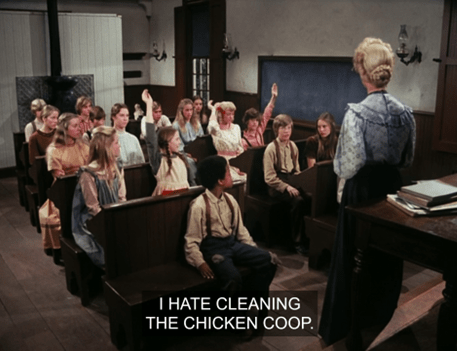

“Now, last week,” says Miss Beadle, “I had you write an essay about the things that you like the most. This week, I thought it might be fun if we wrote an essay about the things that we dislike the most.”

Even before this goes anywhere, we suspect this is a bad line of questioning for these students.

WILL: For God’s sake, Beadle, it’s the Nineteenth Century. They’ll all say their friends and families died in horrible tragedies. Won’t you feel great then?

ROMAN: Yeah. “I dislike having to walk home in a blizzard on Christmas Eve.“

The discussion actual starts out okay. The Mean Kid with Very Red Hair raises his hand, and Miss Beadle says, “Yes, Carl?” even though in “Little Women” this character appeared in the credits as “Teddy.”

Incidentally, this is at least the fourth character named Carl we’ve had on this show.

I would argue there are at least two more, but the evidence for that is less conclusive.

Carl/Teddy says, “I hate cleaning the chicken coop.”

Sigh. This fucking kid needs an attitude adjustment, if you ask me.

If you think this is harsh, recall: First he was a prick to Willie about his ideas for the school play.

Then he dumped whitewash over Willie’s head.

Finally, he goaded Seth Johnson into the horse-training exercise that led to him brutalizing Spotted Eagle.

And now this!

The Bead, however, forgetting all these things, seems delighted with his answer.

She calls on Willie then, but when he says he dislikes “my sister,” she sends him to the corner.

OLIVE: She’s getting pretty trigger-happy about sending people to that corner.

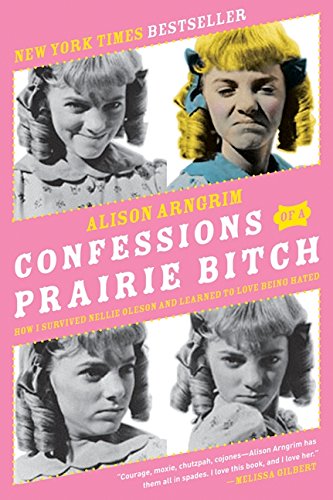

We noticed this is another episode in which Nellie appears but has no lines. I’ll have to thumb through my copy of Confessions and see if Arngrim mentions the reason anywhere.

Then Miss Beadle then calls on Solomon. He literally has the face of an angel, doesn’t he?

She asks what he dislikes; he thinks a moment, and then he says: “Being a n───.”

It’s a simple statement, but it’s about as devastating as it gets for 20th-Century TV, folks. 7+ or no 7+!

Now, it’s true that word has had different impacts at different times. In Nineteenth Century America, I doubt a roomful of white people would be stunned into silence by it the way Miss Beadle and the kids are.

But “The Wisdom of Solomon” was made in 1977, by which time sensibilities around its use had changed dramatically.

Today, as I said, you’d never hear it used on a family show, or in anything really, unless the point is for the audience to be appalled by it, which of course is the intent in this episode, too. Some would view Little House’s use of the word as quite bold. It’s hard to deny this story’s impact would be muffled without it.

At the same time, I find it baffling that so many people fail to see the parallels between how Black people have been treated by mainstream American culture and what we’re seeing with other groups today. (Well, I should maybe say “with other groups AND Black people today.”)

Here’s a good example. As I’m writing this, I’m aware that the venerable genius Elon Musk said the other day that not addressing transgender people by their preferred pronouns is “at most rude.” If Musk and Twitter were around in the 1960s, would he have described applying the N-word to Black people the same way? I expect he would have.

And in those days, “ordinary, decent” people showed up in droves to protest schools for opening their doors to Black families, just like they’re protesting schools (and companies) that acknowledge LGBTQ families today.

What’s the difference? Well, you may see your own differences, but for me the main one is simple. The people who attacked the civil rights of their fellow Americans in the 1960s were listening to bigots then, and the people attacking them today are listening to bigots now.

And of course they’re all on the wrong side of history. Hard to believe we’re going through all this shit again, but whatever.

Anyways, the Bead instantly realizes maybe this wasn’t such a jolly game after all. (I could have told her that.)

To their credit, nobody in class laughs; which I find kind of doubtful. We’ve seen how most of these kids are the dregs of humanity, unable to contain their mocking laughter even when they know they’ll be punished for it. (I sympathize.)

But this time, Cloud City Princess Leia and Pigtail Helen bow their heads in shame.

Even Willie appears sobered by Solomon’s statement.

How they got out of this awkward moment is something we’ll never know, because then we cut back to Mankato, where Charles is chatting with some old geezer in the street.

He crosses to the porch of the grocery store again.

One of the first things his investigation reveals is that Mr. Kramer is still a dick.

Charles says, “It’s about that little Black boy that was here yesterday” (italics mine).

Well, that settles it: They have forgotten where Mankato is.

Mankato is eighty miles from Walnut Grove, so unless there’s a wormhole between the two places, it would be impossible to travel between them in a single day by wagon.

Charles offers some additional information, including Solomon’s name, but when he asks if Kramer if he knows where he can find his family, the guy is like, Are you crazy? (He’s a jerk, but I think that’s a fair response.)

Disappointed, Charles moves off . . . and we see he’s being tailed by Solomon’s brother. (How he got to Mankato is also unknown.)

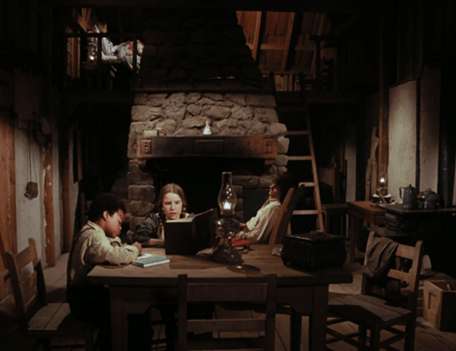

Cut to the common room of the Little House, where Laura and Solomon are looking at books and Pa has fallen asleep in Ma’s foot-amputatin’ chair.

Mary, having zero interest in this episode’s plot, is upstairs reading in bed.

Carrie’s whereabouts are not revealed.

Ma says it’s bedtime, and when Pa wakes up and asks what time it is, she says 9:00.

OLIVE: How does she know the time? They don’t have a clock.

ROMAN: Charles must have a watch.

WILL: We never see him using one. They were expensive. Plus, she didn’t look at a watch.

DAGNY: She probably just gauges time by her Circadian rhythms.

OLIVE: Yeah, or maybe her monthly cycle.

Pa takes Solomon out, and Laura tells Ma she’s experiencing liberal guilt over Solomon’s lowly social status.

Ma, who’s doing embroidery, says yes, despite being poor dirt farmers, they are better off than a lot of people. (Another attitude people seem to have forgotten how to summon up these days.)

Good scene now! Out in the soddy, Pa says goodnight to Solomon, but before he goes, he’s like So . . . I heard you used the ol’ N-word at school today. (Paraphrase.)

Solomon, who by now no one needs me to tell them is one smart cookie, says he realized too late his comment might make the white people uncomfortable.

But, he adds, “It’s the truth. If’n I was white, my pa would still be alive. Being a n─── killed my pa.”

He goes on to say his father died in his thirties, his body worn out by a lifetime of slave labor. At this point I’m just going to give you a chunk of dialogue verbatim, because the writing is very good:

PA: Those days are over. You’re going to start a new life now!

SOLOMON: Ain’t nuthin’ over. Laws don’t change nuthin’! You answer me somethin’, sir.

PA: Yeah, if I can.

SOLOMON: Would you like to live to be a hundred?

PA [laughing]: Sure I would. It’s not very likely. . . . I mean, I guess all of us’d like to live to a ripe old age.

[A Fourteenth-Century expression – a “ripe old age.” – WK]

SOLOMON: Would you rather be Black and live to be a hundred . . . or white, and live to be fifty?

Charles is stunned by this question. We can tell, because David gives us “stunned” music.

Solomon, knowing his point landed just right, looks at Charles flatly. (See what I mean about Todd Bridges being fantastic?)

Embarrassed once again, Pa suddenly says goodnight and exits.

WILL [as SOLOMON]: “Hee hee! That one gets ’em every time.”

Then we return to school. I think I hear the harpsichord, which for unknown reasons symbolizes education on this show, in the orchestral mix once again.

Tartan Nellie is standing at the beginning of this scene, but the Bead says, “That’s very good, Nellie,” and then she just sits down . . . again without saying anything!

Sorry, Nellie worshippers.

Then Miss Beadle calls on Willie, asking him to spell bird. He blows it, spelling it burd (like turd).

OLIVE: Willie doesn’t know how to spell “bird”?

Indeed, Willie’s intelligence is inconsistently depicted in these stories. We know he has behavioral issues, but the last time he received his report card, his grades were all Bs, so he’s not a dunce.

Then the Bead calls on Solomon, who spells it right.

DAGNY: I don’t know how she does it, but the Bead is freaking EXCELLENT at teaching people to read in a matter of days.

WILL: Not just her, all the women on this show! Remember Ma and Dumb Abel?

ROMAN: And yet, Mr. Edwards is still illiterate.

Hilariously, as Solomon spells the word, Laura mouths the letters along with him.

After Solomon answers correctly, Nellie gives Willie a disgusted look. We’ll give her the benefit of the doubt this time and say it’s not the kid’s race she’s reacting to, but the fact that he showed up her family in the Bead’s pop spell-off.

Bizarrely, Miss Beadle isn’t satisfied by Solomon’s performance, and demands he immediately spell a second word with a higher degree of difficulty: cowboy.

Solomon struggles a bit, and we see Not-Joni Mitchell and Cloud City Princess Leia have been won over by the little rapscallion: They mouth the letters as well, clearly rooting for him.

Mary’s also moving her mouth, but it doesn’t really seem to match what Solomon’s saying. (I suppose maybe she’s not sure how to spell “cowboy” either. She doesn’t know the difference between geology and entomology, after all.)

Then again, she is the second-smartest kid in the state of Minnesota.

Eventually Solomon gets it, and Laura jumps up and cheers. A little much, but I found it charming.

Pigtail Helen, however, looks appalled at Solomon’s victory. (That’s a fact we’ll file away for future reference, I guarantee you.)

Miss Beadle abruptly dismisses everybody then, but Solomon and the Ing-Gals loiter about afterward.

Laura’s in a chatty mood, which must make the Bead feel threatened, because she suddenly reminds her who’s boss.

The kids leave, and we get a good look at Solomon’s trousers, which are all patched up.

DAGNY: I refuse to accept Ma would let him wear those pants. She would have made him new ones right away.

Cut to the barn, where Pa is fooling around with a saddle or harness or some such thing.

Laura, meanwhile, is reading aloud:

Under the bludgeonings of chance,

My head is bloody but unbloughed.

DAGNY: Oh, is she quoting John Junior’s poetry?

(It’s actually unbowed in the poem, but Melissa Gilbert says “unbloughed,” which is cute.)

Really, what she’s reading is a weird but good little poem called “Invictus” by the British poet William Ernest Henley. I like to consider myself well-read enough in old stuff like that, but I wasn’t familiar with it. It’s actually the only thing Henley wrote that’s sort of well-remembered.

He only had one leg – a fact which inspired the iconic pirate character Long John Silver, created by his pal Robert Louis Stevenson.

“Invictus” is clearly the poem Laura will recite to atone for her wickedness, and she continues:

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade . . .

“Invictus” is a dark little number. The jist is, “Life is the pits, but that’s okay because people have the stuff to overcome it.”

Or, if you’re of a more religious bent, “Since people have souls and free will, they can get to Heaven and away from this shithole we call Planet Earth.”

Or something along those lines. It wasn’t published until 1888, though.

Anyways, Solomon says the tragic imagery reminds him of the “grievin’ songs” of his people back in the South.

He tells Laura a bit about the women who sang them, then quotes one of the songs:

Death is the robber, but it can’t steal me

Cuz I’ve been called by the Man from Galilee

Now, I could find next to nothing about this song online, except one mention that attributes it to Kurt Vonnegut! That can’t be right, can it?

Solomon continues:

Lord, I never been up, and I’ll never go down,

Cuz my soul is Heaven-bound.

Todd Bridges brings the fucking house down in this one, if you’ll pardon the expression.

ROMAN: My God, they gotta get rid of this kid or he’ll take over the whole show!

DAGNY: He’s a good enough actor for sure.

The music swells up. The tune more than a little resembles “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” (a classic Spiritual).

DAGNY: Rose is pulling out all the stops.

Laura and Pa are deeply moved. So is Ma, who we notice has been lurking in the background the whole time.

Ma leans forward and whispers to Pa, “That boy may stay with us forever.”

OLIVE [as CHARLES]: “We won’t keep him permanently. When a white kid comes with the exact same story we will, though.”

That night, Solomon lies in bed, reading his McGuffey and laughing. If he thinks that’s funny, wait till he discovers Little Willie!

Suddenly, Solomon actually hears footsteps approaching the soddy. (That’s a bit much, I think.)

(That bothers me, for some reason.)

Anyways, it’s his brother!

First thing the brother does is ask Solomon if he’s signed himself into indentured servitude – a strange question which I’d explain here, but let’s face it, we’re running long today and nobody wants that.

The brothers have a brief argument, during which it comes out the older brother’s name is Jackson.

Jackson says he can’t manage things back in Emmetsburg by himself anymore.

And when Solomon starts talking about school, he says bitterly, “It’s crazy for a Black boy to think about schoolin’ and books and figurin’!”

DAGNY: He’s got a Pinky of his own peeking out from under his shirt.

Solomon says, “I wanna learn to read! I wanna know things, more than just corn comin’ up, or how to mend a harness.”

(The dialogue really soars at times in this one.)

Jackson says there’s no point in advancing one’s self, because even if Solomon got an education, he wouldn’t be accepted to do anything but farmwork.

Solomon says, “Is that all we good for, Jackson? Working the field day after day?”

Jackson says, “You think things gonna get any better cuz you can read? You think anything’s gonna change? It ain’t – white folks ain’t gonna let it change. . . . What you think you gonna be, boy? Some kinda doctor or lawyer or somethin’?”

Solomon says, “I can be anythin’ I wanna be!”

With a trace of cruelty, Jackson replies, “You wanna be white, boy? Can’t be that.”

I could quote the dialogue from this scene all day, but we’ve got to move forward.

Solomon is annoyed by this argument, and says if he’s taken back by force he’ll just run away again.

Jackson nods, then hands Solomon a package, saying, “Mama made this for you. She said make sure you wear it.”

DAGNY: Is it new pants? I hope so.

Then, pointedly not taking Solomon away by force, Jackson leaves.

Solomon opens the package and finds a woolen of some sort. Scarf? Sweater?

The next morning, Solomon is running late for school, so Pa drives him into town.

Oh, I almost forgot to put this in: There’s a shot at the barn before Pa takes off where if you look under and behind the tree, there’s a dog or something that goes running off up the hill.

Also, you can see a jet contrail in the sky above them.

Arriving in Walnut Grove, they see Doc Baker and Dr. Tane, the Reservation doctor, loading boxes onto a wagon. Presumably these are the sample medicines they discussed earlier.

WILL: Dr. Tane, Medicine Woman!

Solomon turns to stare at Dr. Tane as they pass.

There are some weird sinister figures up on the hill, but we learn nothing of them.

Solomon says to Charles, “That Black man’s a doctor?” and when he’s dropped off, he goes over to see him, saying to himself, “I’ll be a doctor!”

WILL: Albert wanted to be a doctor, kid, and look what happened to him.

I must note that Dr. Tane is a very cool character by this show’s standards. He kind of seems like he wandered in from another show or movie, in fact.

Tane is played by an actor with the aristocratic-sounding name of Don Pedro Colley.

He appeared in Daniel Boone, Beneath the Planet of the Apes and The A-Team.

He also was in Larry Cohen’s Black Caesar . . .

. . . a blaxsploitation zombie movie called Sugar Hill that’s going on top of my list right now . . .

. . . and a weird early George Lucas film called THX 1138.

He was also in a Disney movie called The World’s Greatest Athlete, about a white guy raised by an African tribe who becomes a track star in America.

I remember seeing it as a small child, and owning a storybook based on it. At the time, I recall thinking it was pretty racist. And I was, like, five years old in rural Wisconsin.

Finally, Colley was in a movie called The Legend of N─── Charley, which created controversy because of its title (among other things).

Don Pedro himself was quoted praising the film, describing it as “the Black Indiana Jones.”

Anyways, Dr. Tane notices Solomon, and gives him a very surprised smile. For this era of the series, two is an enormous number of Black people to find in Walnut Grove simultaneously.

Solomon tells Dr. Tane he’s working for the Ingallses and attending school in Walnut Grove Proper.

Solomon asks Tane if he’s a doctor, and he smiles and says, “Oh, after a fashion.”

The first Black doctor in Minnesota was actually a Dr. Robert S. Brown, who opened a practice in Minneapolis in 1898.

However, since Dr. Tane says he’s a doctor “after a fashion,” we can assume he was trained but not actually credentialed, and this would explain why he was ignored by the history books until Michael Landon & Co. brought him to our attention.

[UPDATE: Since writing this recap, I’ve learned that Dr. Tane was inspired by a real figure – a Dr. George Tann, who was a Black physician the Ingallses knew in Kansas. He only appears in the unexpurgated Pioneer Girl, but he played a very important role – he delivered Carrie!]

Solomon asks Dr. Tane if he’s Walnut Grove’s doctor.

WILL [as DR. TANE]: “Let me tell you something. This town is in the grip of a man called Baker.”

WILL: They should give Doc Baker and Dr. Tane a spinoff and call it “High Doc-Tane”!

Actually, Tane laughs and says he’d never be allowed to be a doctor to white people. He says he works on the Reservation because “ain’t no white doctors gonna do it.”

Now, today, there are two nearby Indian Reservations about equidistant from Walnut Grove: Upper Sioux to the north and Lower Sioux to the northeast.

They weren’t both designated formal Reservations at the time of this story, but both areas had been declared Indian territory, or “Indian Agencies,” by the U.S. government in 1851.

However, you’ll recall from “I─── Kid” and “Survival” that this series takes place during the Sioux Wars, an extended period of violence and attempted genocide stretching from the 1850s through the 1890s.

In 1876 (if that is in fact when this story is set), the fighting was largely occurring in Dakota Territory, not Minnesota.

Now, you’ll also recall we figured Spotted Eagle and his family lived in Dakota Territory, not Upper or Lower Sioux; but that’s mainly because his mother was a teacher at a boarding school, and neither Upper nor Lower Sioux had one.

I’d love to hear from anybody who knows more about these matters, naturally.

Anyways, Dr. Tane asks if Solomon has a family – a question he’s pretty sick of answering by this point.

Solomon dodges the question, figuratively, then dodges it literally by running off to school.

We then cut to Charles arriving home – after dark, again supporting our theory as to the time of year.

He finds Solomon didn’t come in for dinner, so he goes out to check on him.

OLIVE: Why isn’t Laura getting jealous? She gets jealous whenever Pa shows interest in anybody else, especially a boy.

Out in the soddy, Solomon tells Pa he “just ain’t hungry,” but Charles says, “You know, Solomon, when people are friends, they have to share with each other. . . . They have to be honest with each other.”

WILL: Oh, I HATE when he does this. Just because you’re an idiot who spills your guts to every stranger on the street, Chuck . . .

Solomon immediately points out to Charles that Dr. Tane told him Walnut Grove isn’t the nonstop racial-harmony festival Charles suggested.

“You just said we gotta be honest with each other,” he adds.

Charles shrugs, once again embarrassed for white people everywhere, and says it’s true.

ROMAN: You know, the townsfolk don’t seem that interested in this whole development. I mean Solomon coming to a white town.

WILL: I suppose they didn’t want it to be a TOTAL repeat of the Spotted Eagle one. Where do you think he went, anyway?

DAGNY: There’s only room for one BIPOC person on this show at a time.

Then Pa, using the same arguments as many Americans today, tries to excuse his neighbors’ racism by stressing what “good folks” they are at heart. He says being set in your ways intellectually means a lot of people won’t consider new ideas. “It just takes time for ’em to change,” he says.

WILL: Whatchoo talkin’ about, Charles?

“And if they don’t?” Solomon says immediately. “We go to the same school, learn the same. But it don’t make no difference. When we done, nothin’s changed. All I’m still good for is walkin’ behind a plow.”

WILL: Todd Bridges is terrific, isn’t he?

DAGNY: Yeah.

“I walk behind a plow,” says Charles.

“That’s your choice!” says Solomon. “I ain’t got a choice.”

A little simplistic, considering Charles’s own low social status, but point taken.

Solomon says his mom and brother taught him to understand the realities of race relations, and Charles shoots him a look.

“There’s some more of the truth,” Solomon says. “I got a family,” he confesses. “My brother came here to fetch me back, but I told him no.”

Solomon has clearly been thinking hard about this. “I was wrong,” he says. “I gotta go back to my mama.” (He is only eleven years old, after all.)

“Why didn’t you tell us you had a family?” asks Charles.

Solomon says, “Cuz I wanted to be with you, pretend you were my family. But it ain’t no good pretendin.’” We see he’s crying.

“I best be goin’ tomorrow,” he says.

Charles looks agonized, as the Rose provides us rich music from the violins.

Pa tousles Solomon’s hair again – an odd gesture – and says (his voice choking), “I’m gonna miss you, Solomon Henry.”

Wow. Reverent silence in the gallery at our house. Our eyes weren’t necessarily wet; but neither were they completely dry.

Then we cut to Solomon, relaxing on one of those strange logs that are strewn all over the place in the Little House on the Prairie TV universe.

Laura suddenly appears. Apparently Solomon will be departing on a stagecoach shortly.

Solomon says he’ll be glad to return Miss Beadle’s most excellent books. He also tells Laura he wishes he could stay in Walnut Grove long enough to hear her recitation of “Invictus” in class. (Who would wish that?)

“But I know you’ll do good,” Solomon tells Laura. (I’m sure he’s just being his charming self. He can’t really mean these things.)

“Thanks to you,” Laura responds instantly.

DAGNY: Did I miss a scene where he trained her in dramatic recitation, or something?

OLIVE: Yeah. It was basically My Fair Lady.

Then Laura, out of nowhere, says, “What’s wrong with people, Solomon? Why can’t they change?”

And Solomon replies, “Maybe they will, someday. Maybe in a hundred years or so, things will be different.”

DUDE!!! This episode, as I’m sure you realize, aired “a hundred years or so” after the timeframe of this story!

(I should say, I apologize, I suppose everybody who reads Walnut Groovy DOES realize this, but I do just sort of have to go through everything. It’s a recap.)

Then we cut back to the school. Miss Beadle is not there, so of course the entire class is staring at the door silently waiting for her arrival, just like I’m sure you did in school when the teacher wasn’t there.

Miss Beadle comes in at last with Solomon, and announces it’s his last day in Walnut Grove.

Solomon has prepared a speech for the occasion. He’s an overachiever, all right.

Solomon says he’s got to go back and join his family, but he’s grateful to Miss Beadle and the kids for letting him participate in this great school.

In tears, he says he’s “thankful especially to Laura, Mary, and Miss Beadle.”

OLIVE: Mary? She couldn’t have cared less.

Solomon gives Miss Beadle a hand-carved sign that reads “Bless This School.”

The Bead starts weeping and hugs him, which is a little much.

Then Solomon looks at Laura out in the crowd and says, “You make that poem sing, now.”

WILL: I like to do that when I have to make a speech, put little jokes in for my friends.

We see Mary is crying too. She looks like she’s been crying for hours, in fact.

OLIVE: Oh my God, Mary! Grow up!

DAGNY: Yeah, I can’t believe she’s crying.

ROMAN: Hey, it’s probably just her incision bothering her.

Then we cut to Pa at the window of the Post Office. A phantom hand hands him something and he says, “Thank you, Grace,” but if that’s really Bonnie Bartlett’s hand I’ll give you a buck.

Charles steps down into the thoroughfare.

ROMAN: Look, it’s Al Swearengen!

Pa hands Solomon, whose eyes are still crusted with tear-glue, a ticket for the stagecoach. (Apparently Pa paid for it, which again is crazy considering they’re broke. Remember how he couldn’t even afford to buy a ticket for Mary, his own child, to go to Minneapolis?)

(And why didn’t the brother take him home the same way he came? Surely he’s still around someplace, unless he made a 177-mile trip just to have one five-minute conversation and then head back.)

Anyways, Pa and Solomon say goodbye.

WILL [as SOLOMON]: “I love you, Charles Ingalls!”

ROMAN [as CHARLES]: “I know. Everyone does.”

And, with “Solomon’s Rondo” swelling up again in the score, that’s it.

OLIVE: They should have smuggled him out of town in a pickle barrel or something.

I love that idea. Bum-Bum-Ba-Dum!

STYLE WATCH: Charles appears to go commando again.

THE VERDICT: Todd Bridges is phenomenal in this, and the dialogue is magical. The message still resonates today, as much or even more than it did in the 1970s.

However, Olive didn’t like it so much. “It was just a bunch of speeches with no real story,” she said.

Longest recap ever, huh? Well, thanks for sticking with me. Oh, and again, if you want to hear Melissa Gilbert and Todd Bridges shoot the shit and catch up, check out the most recent episode of Modern Prairie’s The Knitty Gritty podcast!

UP NEXT: The Music Box

Another great recap. Loved the mock~up of the “twilight zone” episode! And I was just thinking of the day that Todd Bridges is the only actor left from “different strokes.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Maryann! I was thinking about that too. He seems like a neat person.

LikeLike

I love these. I look forward to them and now have them coming to both my email’s so I won’t miss them. I’m a 54 year old gay man who started watching little house when I was 6 years old. I stayed with it. I have read all the books by the cast. I really love the walnut groovy post. The humor and research are highlights. So…thank you.

Toby Gollihar Portland Oregon

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Toby!!! I’m so glad you like it. 😊

LikeLike

I loved this one! Laughed outloud at some of it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m divided about this one. On one hand, it effectively dramatizes the psychological effects of racism on black children. On the other hand, I find the portrayal of Solomon a bit condescending. Spotted Eagle was also the victim of racism, but he had a sense of self, a confidence that he was as good as any white kid. But Solomon seemed a bit too eager for the approval of Charles and white people in general. OK. They’re two different characters. But I thought “Indian Kid” had the better anti-racist message.

Watching the Gold Country episode now and wondering if Charles had ever successfully harvested a crop during the whole series. His farm seems more like The Ingalls Chicken Coup and Egg Factory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fair observation – I find Bridges so likable and the story’s bigheartedness enough to overlook some of its issues. As for your comment about Farmer Chuck – 😆

LikeLike

My housemates in suburban New Jersey run a farm in the backyard that produces exponentially more food in one season than the Ingalls farm produced in almost a decade. Maybe it’s the more humid climate. We have hail, frost and rain here so that wouldn’t be it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And now you’ve gotten ahead of me! This makes me sad. I’m grateful for your interesting comments and glad you’re enjoying Walnut Groovy. – WK

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m looking forward to your recap on The Election and the victory of the Anti-Bullying Coalition in Walnut Grove.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To be fair, Spotted Eagle in a Sioux community where he was well-accepted and presumably taught about his self-worth and to value his culture and identity. Meanwhile, Solomon was taught from an early age that his background would always be limiting, even dangerous to him, and that he should always walk on eggshells and never expect to be on the same level as others. That probably had an impact on how he viewed his situation, even as he tried to defy his family’s statement that he could never be everything a white person could. He knew he was in a tight situation and wanted to go out of his way to be accepted, whereas Spotted Eagle mostly wanted to be left alone and practice his customs in peace.

LikeLiked by 1 person

WordPress.com / Gravatar.com credentials can be used.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, you’re not wrong

LikeLiked by 1 person